Treating raw materials

Ceramic comes from the Greek word “keramos” which means clay. Along with glass and enamel, it is one of the “kiln work” arts, as the use of fire makes irreversible changes to the material.

Ceramics can be broken down into four main families : pottery, faience, stoneware and porcelain.

Its preparation takes place in four main steps. The preparation of the paste, its moulding or modelling, its decoration and its firing.

The raw material, i.e. the clay, is crushed with water. Since the 20th century, ball mills have been used, which succeeded stonemills. These machines are used to obtain the desired fineness of the grains. The material obtained is filtered then pressed in filter presses. The clay then undergoes a final operation: de-airing. This removes all the air bubbles that might be inside the clay or paste. Formerly, this was done by foot, hence the name of the “marche à pâte” (paste treading) workshop still seen in some manufactories that made their own paste. The clay comes out of the machine in the form of “boudins” (sausages), which are then cut into small round biscuits known as “camemberts” (cheeses). The clay is then ready to be moulded.

Moulding

The craftsman uses a potter’s wheel or the casting technique, either by pressing or slipcasting. Until not long ago, the moulds were made of plaster, but they have now gradually been replaced by synthetic materials. Since the second half of the 19th century, the porous nature of plaster has been used to make the finest objects, by slipcasting. The porcelain paste is liquefied and poured into a cast. Through capillary action, the water contained in the paste penetrates the plaster, causing the edges to harden gradually. Once the desired thickness has been obtained, the extra paste, known as the “slip”, is discarded.

Decoration

Different colours are obtained with metal oxides : each oxide produces one or more colours after firing. The basic oxides are cobalt, which produces blue ; copper, which can transform into green or turquoise ; iron, which comes out yellow or red, and manganese, which turns brown. Pink or purple are obtained with gold chloride. Until the 18th century, the decoration was applied with a brush.

In the 19th century, as companies moved towards industrialisation, intaglio printing techniques were used, in which a monochrome decoration could be printed using a copperplate. This monochrome decoration was finished off by hand with colour (“illumination”). Chromolithography solved this inconvenience by printing a decoration, using the same number of stones as the number of colours required. This technique, which was well developed by the end of the century, used a palette of 18 colours. Modern decalcomania uses silkscreen printing, which is based on the same principle but uses silkscreens, followed by synthetic materials.

To apply the decoration, two methods are used. The first is called high-fired decoration and the second is called low-fired decoration.

Firing

The firing of ceramics is characterised by the fact that it is completely irreversible.

Before being decorated, the objects undergo an initial firing, known as “biscuit” firing, at 900°, the purpose of which is to dry out the moulded object, before it is glazed.

Firing of hard-paste porcelain must be at 1400°. Since the 18th century, kilns have been built that are capable of reaching this temperature. In Sèvres, in 1769, round kilns were built. Initially theses kilns used wood, but from the 1850s, coal was used. Then in the 1960s, the use of gas-fired kilns became the norm.

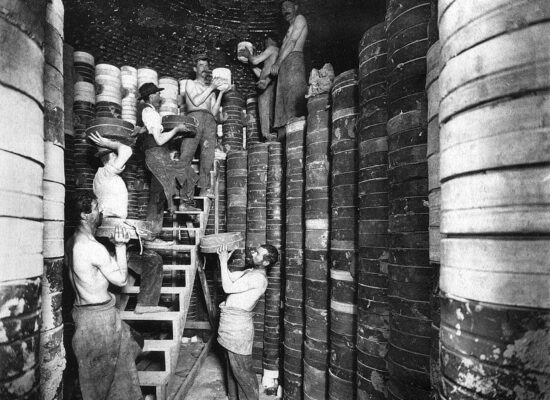

Placing the pieces inside the kiln is a delicate operation. To prevent porcelain objects from collapsing, they are placed in refractory clay containers or “saggars”, which can be easily stacked up.

Contemporary gas firing considerably reduces the chances of deformation, marks or breakage.