Pottery

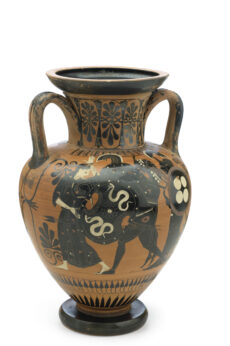

Pottery is made of clay, moulded and fired at around 600-800°. Firing at a low temperature produces a porous material.

It is probably the oldest craft known to man. The technique has been used throughout the centuries up to the present day. In the Middle Ages in Europe, items were often covered in a lead-based coating, to make them watertight.

The oldest objects in the museum go back to the 12th century BC and go as far as the 19th century AD. The museum also contains some very interesting examples of non-European pottery, from South America and North Africa.

Faience

Faience (glazed earthenware), is one of the four main families in ceramics, along with pottery, stoneware and porcelain.

Faience is clay that is moulded then immersed in tin enamel, known as tin glaze. This coating improves the watertightness of the objects. When it is fired, the tin gives the enamel a white colour upon which artists can add various decorations.

Opaque tin enamel was discovered in Mesopotamia towards the 9th century AD. This technique was brought by the Muslims, via North Africa, as far as Spain, where faience has been produced since the 11th and 12th centuries. From Spain, the technique travelled to France (via paving) and especially to Italy, where the princes of the Italian Renaissance competed to produce the most beautiful majolica. The roots of the word faience come from the name of the Italian city of Faenza.

Italian influence was very significant throughout the 16th century through artistic trade and favoured by commercial trade. The faience technique therefore spread throughout Europe. The 17th century saw the emergence of Delft earthenware in Holland, also inspired by Italy. The following centuries were marked by the development of faience manufactories in France.

The main stages in the history of faience are very well illustrated by the museum’s collections.

Stoneware

Stoneware is a ceramic made from clay with a high silicon content known as “stoneware clay”, which is fired at around 1250°. The clay therefore reaches the maximum vitrification point. Stoneware is opaque but the intense heat gives it a very compact texture which makes it watertight. It is usually a grey or brown colour.

This technique was developed in China. In Europe, the earliest stoneware goes back to the end of the medieval period, in Germany. The decorations were often done in cobalt blue, the only oxide that can easily withstand high temperatures. Stoneware can be covered in a salt-based varnish which gives the surfaces a thin, shiny coat. In the 17th century, the development of faience and porcelain led to the relative abandonment of stoneware, although it once again gained popularity from the 19th century onwards.

The collection includes Chinese stoneware, as well as German and French stoneware from the Renaissance. The museum also has a remarkable demonstration of artists’ work from the late 19th century which, following Jules Ziegler in the mid-19th century, used stoneware as a specific means of expression up to the 20th century

Porcelain: composition and appearance

Porcelain is a paste consisting of kaolin (50%), feldspar (25%) and quartz (25%). Kaolin is a type of clay, which owes how fine it is to the disintegration of feldspar, and has the notable quality of remaining white after firing. Able to withstand temperatures up to 1400°, the material becomes vitrified, which is what gives porcelain its second remarkable feature : translucency.

Known in China since early Christian times, probably during the Tang era (618-907), kaolin was only discovered in Europe in the early 18th century in Germany.

With the Renaissance and the discovery of the sea routes, Chinese porcelain became a point of reference for European ceramists, who continually tried to imitate it. In the absence of kaolin, they produced a material with a similar appearance, soft-paste porcelain (a blend of different clays, but without kaolin).

The museum owns some remarkable hard-paste and soft-paste porcelain pieces (monochrome, celadon, or Chinese “blue and white”, soft-paste Sèvres porcelain and the early hard-paste European porcelains from Meissen, Saxony and France), enabling us to follow the major stages in the global history of this much-loved ceramic.